Developing a Digital Public Infrastructure repository for best practices and regulations should be the job of India as G20 president today and part of the G20 troika till 2025, write Manjeet Kripalani, Harshit Kacholiya and Madhumitha Prema Ramanathan.

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) encourages and accelerates private and public innovation and provides digital access and equity to the very poorest – a G20 goal. India has made this a central offering of its G20 presidency, showcasing how developing and developed countries may benefit from the technology and the business model. India’s DPI, based on the India Stack open source framework, has grown over ten years. It is a unique entrepreneurial and volunteer effort by citizens enabled by the government, to bring seamless, reliable, replicable and low-cost digital inclusion, tested at a sub-continental scale. This independent and robust ecosystem has lowered the cost of transactions for individuals, businesses and governments and permits the safe sharing of personal data without compromising privacy.

DPI and Public and Private Innovation

It has spawned both private and public innovation. Fintech and e-commerce have led the private sector innovation in India, putting the country on the list of the top three unicorn-producing nations in 2023 – over 100 so far. The public sector’s use of DPI has led to government services, delivering them efficiently and transparently. An example is the transfer of direct benefits to citizens, which has saved India $33 billion by preventing leakages in the transfer of subsidies, and which funds which have been reinvested to improve health, sanitation, education, etc. DPI does all this while keeping nations digitally sovereign. This article explores how DPI creates public and private innovation and compares it with private digital offerings, which also work at scale but for commercial profit and are not always in the national interest. The private sector in India used DPI well especially in Fintech and e-commerce. Innovating on the DPI tracks has created new businesses and cost-effective service delivery, which in turn has provided access to and also provided opportunities for young talents, and eventually, powered economic growth. Examples abound. Google Pay created a smartphone payments app, the first of its products based on the Indian DPI, and the first-ever product Google created specifically for India. Other such Google products are now being developed for and tested in India – for global use.

NBFCs and DPI

Banks and Non-Banking Financial Corporations (NBFCs) have been significant beneficiaries of DPI. With 1 billion digital IDs generated along with the e-KYC and e-Sign framework, India has reduced a bank’s cost for on-boarding a customer from $23 to $0.15. It has allowed for 3 billion identity authentications for private transactions, including completing 150 million distinct digital KYC reviews. In 2022, 89.5 million real-time online transactions took place in India – 46% of all worldwide real-time payments. Brazil processed 29.2 million, China 17.2 million, Thailand 16.5 million and South Korea 8 million. This has improved the scope of lending. In India, a consumer or even personal loan can take as little as a few seconds to four hours to be approved. It includes the process of the consumer giving the lender access to personal financial documentation, through a DigiLocker – a digital locker where all documents from school certificates to health reports to income certificates can be stored for use whenever needed and in any geography. It enables commerce and saves the citizen time, money and logistical difficulty.

The impact on the GDP of a largely cash-based economy being formalised, is evident. Since 2020, adaptation of DPI by Indian ministries for subsidies alone has saved over 1% of GDP or $33 billion – monies that were used to expand and better use government schemes for poverty alleviation. Additional money in the hands of citizens expands the economy.

In the summer of 2021, India saw a blossoming of e-commerce start-ups, all of which have used DPI for their benefit. That year, India had 37 unicorns, which have grown to 107 in 2023, and attracted venture capital of $25 billion during the year. The cost and time of bringing customers on-board has reduced across sectors. For example, large banks can now onboard customers in 1 hour instead of 6 days; large telecom players can provide a SIM card in 4 minutes instead of 24 hours, and large asset firms can onboard customers in 2 minutes instead of 4 hours. All of this frees up capacity and enhances customer experience.

Collaborations

The collaboration between public and private sectors in digital public infrastructure is powerful and has had a multiplier effect. This is visible in countries such as India, Estonia, Ukraine, where a variety of models exist. Two are the most effective: one, the creation of Account Aggregators and use by foreign private tech players. Account aggregators are private players, licensed by India’s central bank, which provide full control to the consumer who wants to share her personal data for various needs. This effort is coordinated by an NGO called Sahamati – a triangular collaboration model. This is not limited to Indian entrepreneurs; foreign private entities like Stripe, a payments platform, can also be an account aggregator – without payment, unlike its business model in advanced Western economies.

Here too, there are global examples – like M-Pesa in Kenya, Pix in Brazil, and DIIA in Ukraine. M-Pesa in Kenya is a small-value electronic payment system accessible from ordinary mobile phones. It is a 2010 collaboration of multinational private telecom players Vodafone, local internet provider Safaricom, the aid agency of the UK goverments and the Kenyan government. Today, half of all transactions in Kenya take place through mobile money, and M-Pesa dominates all of it. Brazil’s Pix is a fast-payment system introduced by Brasil’s Banco Central in 2020. It is similar to India’s UPI and is also growing exponentially. In 2021, Pix saw 1.2 million transactions per month, a fourth of India’s UPI, but the value of the transactions of both was an estimated $100 million each. Pix now provides 85% of its population access to financial services and is being used for social programmes like Cad Unico and Bolsa Familia. Ukraine’s DIIA is a DPI established in 2020, to enable the private tech sector to collaborate in innovation in a Digital Free Economic Zone. During the war, DIIA has helped citizens of Ukraine to digitally retain key identity documents which may have been lost or destroyed in the upheavals. This has particularly helped in their mobility and search for safety in other countries. Based on the success seen in FinTech driving financial inclusion using DPIs, India is now taking a giant step forward: implementing DPIs in the health, education and agriculture sectors. Agri-techs were already ready in February 2023 when Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced DPI for agriculture. The collaboration of the private sector has already been sought, through accelerator funds for startups in rural areas. The next green revolution is expected to be a digital green revolution.

Challenges

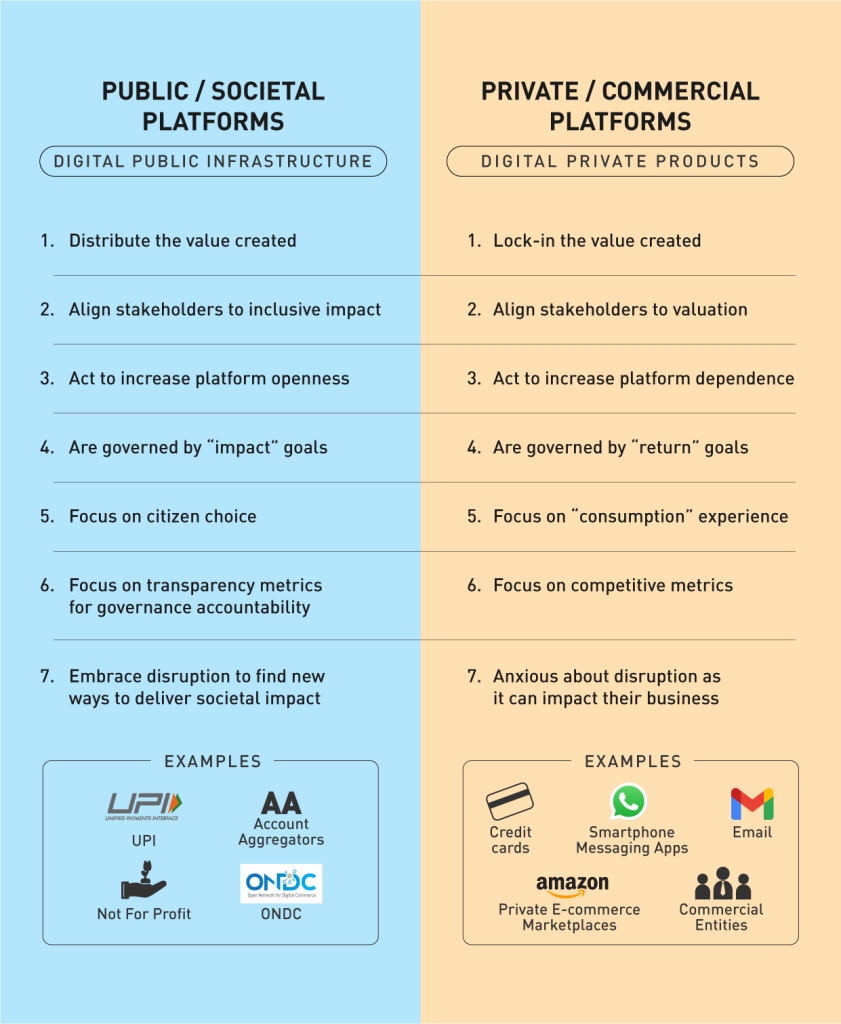

Of course, there are challenges for both the public and private sectors. The most significant is the inherent conflict between private sector interests and the pursuit of public welfare. Private sector investment brings undeniable benefits, but the predominant focus is on profit maximisation and can inadvertently create exclusionary barriers for certain groups, perpetuating unequal access to essential services for individuals and communities. The omnipresence of some private sector platforms such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Alibaba, Facebook, and Tencent, results in their projecting an extensively-used private product with the public good. Hence, the need for building a ‘Good DPI’ like India Stack, and knowing the difference between a digital private product/digital public infrastructure becomes essential. Issues of excessive control over DPI also exist, which can limit public oversight and accountability, and potentially result in monopolistic practices, particularly in the era of artificial intelligence. Strong legal protections enhance innovation.

India has already set this in motion with procedures to protect data-sharing for consumers, businesses and service providers. It includes the key principles of Permission (free consent for sharing data), Protection (of sensitive personal information) and Privacy (secure and encrypted). This year India will introduce another DPI called the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA), a framework that provides granular control to data owners over sharing personal data through unique technology-enabled legal rules.

DEPA will then move into its second phase, which is the foundational model for AI applications, whilst preserving privacy and ensuring regulatory compliance. This will drive ethics-based AI offerings that benefit individuals, enterprises and society. The challenge for G20 countries, therefore, is to understand the value of DPI to their societies, overcome their monopolistic digital capture, and provide a secure ecosystem for public and private innovators to build open source DPIs. The institutional role of the G20 in fostering innovation and growth through DPI is four-fold:

Encourage governments to finance DPIs and thereby:

- Create a robust global ecosystem.

- Develop global standards for DPI.

- Build a DPI repository for best practices, including regulation.

The Way Ahead

To achieve the above, and protect the vast amounts of data generated by DPIs, individual governments must establish strong data protection laws and regulations to ensure that data is collected and used transparently and securely. India’s DigiLocker and Ukraine’s DIIA is a step in that direction, and the EU has pathbreaking consumer data protections in place. To facilitate innovation and safety, a clear line of communication must be established between the public and private sector, encouraging the sharing of information and expertise, and embedding a culture of collaboration.

DPI’s success depends on its standardisation and interoperability. There are already several suggestions within the G20’s trade and investment working group to develop standards for digital trade – an area where innovators will be present. The G20 Digital Working Group can align with the Trade and Investment Working Group to develop standards. Global standards for DPIs on identity, payments and data will help countries to develop an ecosystem, where one country’s DPI and its innovators will be able to seamlessly speak with and be interoperable with another country’s DPI. Developing a DPI repository for best practices and regulations should be the job of India as G20 president today and part of the G20 troika till 2025. India is best positioned as a pioneer of DPI and software heavyweight. Close collaboration with national regulators on the same will result in flexible regulatory frameworks that adapt to rapid changes in technologies and emerging risks.

Manjeet Kripalani, Executive Director and co-founder, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Prior to this, Manjeet was the India bureau chief for Businessweek magazine, New York, and has won several awards for her work. In her political career, she worked with Republican candidate Steve Forbes during his 1995-96 run for U.S. President.

Harshit Kacholiya is a Political Science Alumnus from Hindu College, University of Delhi. He is a LAMP Fellow and is currently, working with iSpirt as a Policy Implementation Executive.

Madhumitha Prema Ramanathan is currently a volunteer at iSpirt, a think tank in India and also the Chief Strategy Officer at Experian India. She has over 15 years of experience in the financial services industry having worked with Goldman Sachs and Invest India in the past. She holds an MBA degree from the Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Author Profile

- India Writes Network (www.indiawrites.org) is an emerging think tank and a media-publishing company focused on international affairs & the India Story. Centre for Global India Insights is the research arm of India Writes Network. To subscribe to India and the World, write to editor@indiawrites.org. A venture of TGII Media Private Limited, a leading media, publishing and consultancy company, IWN has carved a niche for balanced and exhaustive reporting and analysis of international affairs. Eminent personalities, politicians, diplomats, authors, strategy gurus and news-makers have contributed to India Writes Network, as also “India and the World,” a magazine focused on global affairs.

Latest entries

DiplomacyJanuary 5, 2026India walks diplomatic tightrope over US operation in Venezuela

DiplomacyJanuary 5, 2026India walks diplomatic tightrope over US operation in Venezuela India and the WorldNovember 26, 2025G20@20: Africa’s Moment – The Once and Future World Order

India and the WorldNovember 26, 2025G20@20: Africa’s Moment – The Once and Future World Order DiplomacyOctober 4, 2025UNGA Resolution 2758 Must Not Be Distorted, One-China Principle Brooks No Challenge

DiplomacyOctober 4, 2025UNGA Resolution 2758 Must Not Be Distorted, One-China Principle Brooks No Challenge India and the WorldJuly 26, 2025MPs, diplomats laud Operation Sindoor, call for national unity to combat Pakistan-sponsored terror

India and the WorldJuly 26, 2025MPs, diplomats laud Operation Sindoor, call for national unity to combat Pakistan-sponsored terror